(NEW YORK) — The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine advisory committee appears set to amend the childhood immunization schedule, including potentially changing recommendations on a shot given to newborns.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is meeting Thursday and Friday. A draft agenda posted online on Monday provides little detail on what materials will be presented or which speakers will give presentations, but does mention a discussion about the hepatitis B vaccine on the first day as well as “votes.”

Although it’s not clear what will be voted on, past comments from Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and ACIP members indicate the universal hepatitis B vaccine dose given just after birth will be at issue.

The ACIP may vote to remove the birth dose recommendation or delay vaccination to a later age.

Public health experts told ABC News there is no evidence to suggest the hepatitis B vaccine is unsafe and that vaccinating babies at birth has been key to virtually eliminating the virus among children.

What is the hepatitis B vaccine?

The hepatitis B vaccine is typically a three-shot series. The CDC recommends the first dose given within 24 hours of birth, the second dose between 1 month and 2 months, and the third dose between 6 months and 18 months.

In addition to all infants, the vaccine is recommended for all children and adults aged 59 and younger as well as adults aged 60 and older with risk factors for hepatitis B.

The ACIP previously recommended that only babies screened and found to be high risk for hepatitis B receive a vaccine, but experts found that screening missed many hepatitis B-positive cases.

“Hepatitis B vaccine was initially recommended for older groups and eventually then for children, but not for newborns,” Dr. Susan Wang, a former CDC hepatitis B virus and vaccine expert, told ABC News. “We have learned over decades now of both the safety and the impact of the vaccine, and it was a very specific decision to move it, not just to infancy but … within 24 hours of birth.”

The ACIP recommended that infants begin receiving the vaccine within hours of birth in 1991 as part of strategy to stop hepatitis B transmission within the U.S.

Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, told ABC News vaccination is important because if a pregnant person is hepatitis B-positive at the time of birth, the infant has an 85% chance of developing an infection.

If the infant develops a hepatitis B infection, they have a 90% chance of developing chronic hepatitis B, which can predispose them to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and liver cancer.

What effect has the vaccine has on hepatitis B cases?

During a Senate hearing earlier this year, Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., a physician, said that before the recommendation was put in place in 1991, as many as 20,000 babies every year contracted hepatitis B from their mothers in utero or during birth.

Today, fewer than 20 babies every year get hepatitis B from their mother, Cassidy said.

Schaffner, who was part of the 1991 ACIP committee that recommended the universal birth dose, called it a “brilliantly successful program.”

“Both from a clinical perspective and a public health perspective, this has been a program that is successful beyond the imaginings of us when we sat around that ACIP room debating this in 1991,” he said. “The cases are just coming down astoundingly.”

Schaffner said if the ACIP votes to delay the recommendation, he is worried some parents will never get their children vaccinated.

“A vaccine postponed is often a vaccine never received, that is sure to happen,” he said. “There will be some children born to hepatitis B-positive mothers who, because they don’t get their birth dose, will slip through the system. They will become infected and, when they get older, they will transmit the infection to others, and we won’t be able to interrupt the transmission of this virus in our population.”

What has RFK Jr., CDC panel said about the hepatitis B vaccine?

During a June interview on The Tucker Carlson Show, Kennedy falsely claimed the hepatitis B vaccine was associated with an increased risk of autism.

Numerous existing studies have examined whether vaccines, or their ingredients, cause autism and have failed to find any such link.

Kennedy and other federal public health officials, such as Dr. Marty Makary, commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, have claimed hepatitis is mostly transmitted through sexual contact or needle sharing, and therefore babies don’t need a vaccine to protect against the infection.

They have suggested pregnant people be tested for hepatitis B and that only the babies of infected patients receive the shot at birth.

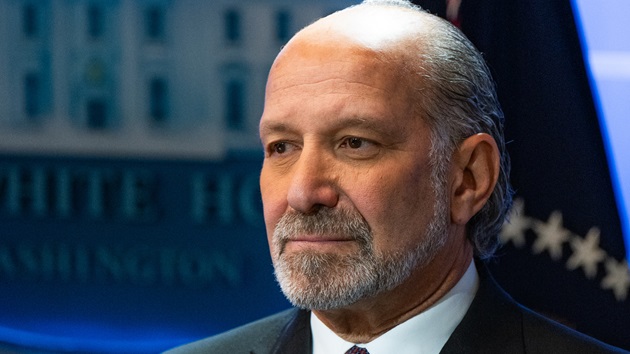

During an ACIP meeting in June, then-chair Martin Kulldorff, a former Harvard Medical School professor, questioned whether it was “wise” to administer shots “to every newborn before leaving the hospital.”

Wang said there are a few reasons why a testing-only strategy doesn’t work, the first being that even if every pregnant person were tested before delivery and only babies born to positive patients were vaccinated, the unvaccinated babies would be unprotected against the virus, which is highly contagious.

Another reason is that not all pregnant people get tested or, if they do, they don’t get tested in time or have receive their results quickly enough, Wang said. Under a testing-only strategy, this could prevent a newborn from getting a vaccine when they need it.

“The hepatitis B vaccine is inexpensive, extremely safe, and has a high value in terms of effectiveness,” she said. “There’s no downside. And again, this has been after decades of studying this and globally, millions and millions of infants getting vaccinated. So, the value and the benefit of it is so far outweighs any possible issue.”

What if the hepatitis B vaccine birth dose recommendation is changed?

Wang compared removing the universal hepatitis B vaccine birth dose to taking a seat belt off in a car.

“The purpose of having the seat belt there is to protect you from the risk of injury and death when you’re in a moving vehicle,” she said. “It’s the same thing with the vaccine.”

Wang explained that the vaccine is given early as a post-exposure prophylaxis in case an infant is infected from their mother, but they can also contract the virus from anyone who is infected, either around the infant or taking care of them.

She added that if an infant is exposed during their first 12 months of life, the risk of chronic hepatitis B infection is substantially higher than if they are exposed during adolescence or adulthood

“If you don’t interrupt transmission, if you don’t cut it off at the pass, namely, at birth, we’ll have hepatitis B-positive people in the next generation, who, when they get into their teenage and young adults and older adult years, will pass it on sexually to others, and we will maintain this virus in our population,” Schaffner said.

Additionally, insurers often rely on ACIP recommendations to determine what they will and won’t cover, experts told ABC News.

If certain vaccines aren’t recommended by the ACIP, it may lead to parents or guardians facing out-of-pocket costs if their children receive the shot. It could also mean the shots aren’t covered by the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, a federally funded program that provides no-cost vaccines to eligible children.

Copyright © 2025, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.

- Video of Clintons’ depositions in House Epstein probe is released - March 2, 2026

- Department of Homeland Security warns of potential attacks amid Iran operation - March 2, 2026

- Your Daily Briefing – March 2, 2026 - March 2, 2026